|

David

Miller is Irish and financial adviser. Living in Brazil since the beginning

of the sixties years, he develops projects of researches, conservation

and regeneration of the Rain Atlantic Forest in the state of Rio de Janeiro,

in Macaé de Cima. This region is one of the important remainder

area of this forest in the state, according to Gustavo Martinelli, Atlantic

Forest Program's

coordinator,

from the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, in the forewords of David's

first book: "Orchids of the High Mountain Rain Forest in Southeastern

Brazil".

|

|

|

This

book, written with Richard Warren and Isabel Moura Miller, has been a

result of research and survey which took 16 years. It embraced 270 species

among 66 orchid genera occurring above 1.000m altitude. His new project

is much more extensive covering the Organ Mountains (Serra dos Órgãos),

since de sea level and took 6 years to be accomplished, more than 600

species have been classified. |

| ON:

David, can you tell a little about your life? David: I was born in Ireland, I did my studies in London, in England and when I was 20 years old, I immigrated to Canada where I stayed for four years. I loved that country, I enjoyed everything it has. Then I came to Rio de Janeiro to help the opening of a Canadian auditor office and I traveled all over the country. 25 years years ago, I was annoyed with multinational institutions and got out to become a "free lancer". Since then, I am here 'freelancing'". ON: How did your interested in orchids start? David: My parents lived in Africa and I grew up with my grandmother and her hobby was the orchids, specifically, I found out later, Brazilian orchids. Just after arriving here, a friend invited me to go Nova Friburgo. I fell in love with the forest where I saw the orchids my grandmother had in Ireland, so decided to stay that same day of 1962. ON: So you has been living in Brazil for more than forty years. How did your project of conservation and survey of the orchids start? David: I purchased in 1964, a very small farm in Nova Friburgo, in Mury. Then, in 1968/69, with that Brazilian economical miracle at full blast, many medium class people came out, constructing country houses every where and calling them "Sweet home", "Here you are", "Three brothers farm", 'Fairy tales" . I couldn't stand this no more and, in l970, I bought another tract of land which is very big, with a big forest that made me to become deeply interested in orchids. After two attempts of marriage, I met Bel who became an enthusiast of conservation and we entirely concentrated ourselves in conservation and in orchids. Before that, however, we decided that, with so many orchids, we should do a book about those from Macaé de Cima and we did "Orchids of the High Mountain Rain Forest in Southeastern Brazil". The first book was a success, we printed the second edition and it could be even a bigger success but Salamandra (the editor) didn't want to print the third edition. As we were at about to do the book on Organ Mountains (Serra dos Órgãos) since Tinguá until São Fidélis, we gave up calculating that we would take just two or three years. It took 6 years. And we did it without patronage, between freelance works. ON: Without any financial support to carry on the project? David: None. |

| ON:Who

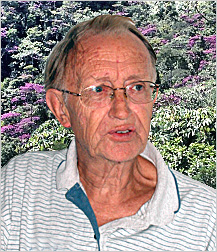

participated on this first project? David: We were three people involved, me, Isabel and a childhood friend, Richard Warren. |

David e Richard (in the extremities) and a guide field |

In

England, we formed a trust, Real Atlantic Forest Trust - RAFT to get funds

and organizer eco-tourism here. By the time of the XV WOC, in l996, we had

150 visitors, among them, 70 Australian people and it was organized by RAFT.

This allowed us to do our researches all l997 round. After those orchidists,

no body came to Brazil during two or three years. We also had the opportunity

of developing a great project in Amapá and we stayed there for almost

a year. The study was about Açaí (Euterpe oleracea - kind of palm) |

|

ON: Richard Warren is one of the co-authors of the

first book, which is his participation in the new project? David: He is Ph.D. in Botany and helped in taxonomy, he stayed here for six months. He has a laboratory to propagate orchids, only species. ON: Coming back to your conservation project. David: We purchased another area in the headwaters of Rio das Flores (River), Macaé river's tributary, which is much bigger, more "virgin", we can say that. Our house is at 1.500m altitude, the whole land is situated at about 1.300m, on the average. There is another land that Bel and I bought in l983, and the house is placed at 1.100m, where we live and breed pheasants and teals to supply restaurants. ON: How the conservation project is being developed? David: The first area was very interesting but it had 30% burnt, obviously, we could not do any with it. We started studies in order to find out the velocity of regeneration, which would be the best place, which would the most difficult, etc. The natural regeneration is the only and the cheapest way to regenerate forest . The only thing you has to do is take a barbed wire, encircle an area and do not allow any cattle to get in (cow ,she-goat, horse), thus you have a very quickly natural regeneration. ON: How was your first experience of reintroducing Laelia crispa? David: This happened in l983, when a work provoked the removal of trees replete of Laelia crispa. We gathered the plants and planted them in different places. We consider as the aim target to induce those plants to produce seeds. Those seeds and the resulting plantules would be reintroduced in the nature instead of reintroducing the reproducer mother-plants themselves. The plants throve and this brought us to do a more extensive salvage operation and we collected at about 100 plants from the trees which were also cut down. During the two first years, we pollinated by ourselves, but subsequently, there is no more need to do it. |

| ON:

This region is comparatively well preserved but it also has degraded areas,

hasn't it? David: There are many degraded areas in the state of Rio, mainly in the anticline of the other side, for example, Nova Friburgo, going down to Paraíba do Sul river. |

| This

area has been devastated by the Coffee cycle. Still nowadays we can see

the grooves, signs of the plantations which were done vertically on the

hillsides mainly to allow the foremen control the slaves' work. With the elimination of the forest, the humus and the vegetal earth were eroded, turning into a semi-desert, the soil is worth nothing, it is a poor pasturage, full of ticks, worms. The half of anticline, since Trajano, is a semi-desert. It is not by chance that the population density is the lesser in the state. |

|

| If

you just fence an area, you will have a natural regeneration in two years,

you will have a some high wood. Only forbidden the entrance of animal, the

humus starts to appear, the most noble trees can enter or be planted. The

noble trees such cedar or cinnamon have lateral root system which doesn't

go down the soil as eucalyptus. The root system is superficial but they

need a layer of humus, dead leaves, vegetal earth, with a minimal deepness

of 50 cm. And this deepness takes 30 years to be formed and it is no use to throw humus because the rain will carry it. The interlacing of the capillary roots hold back every thing, it retains the water. We found all those things out all along those 30 years. We realized that the south face is much easier because of the humidity level since the sun doesn't touch it during six months of the year. Regenerating this face is three time quicker than regenerating the north face which is the most difficult because it is burnt by the sun all year round. The west face has some characteristics, the east face has another. The degree of pluviosity has also an influence. We studied it in loco, observing. The discovering of the required conditions for the orchids was very fascinating. We find out that only after a certain time, when the layer of humus has a certain deepness, allowing a constant humidity raising until 2 or 3 m high, we start to see bromeliads and the pioneer orchids coming in the regenerated forest. The interconnection between the three keys, humus, pioner-trees and bromeliads is the responsible for raising the humidity which allow the establishment of epiphyte plants in the highest parts. If the orchids are not there, the forest is not healthy. |

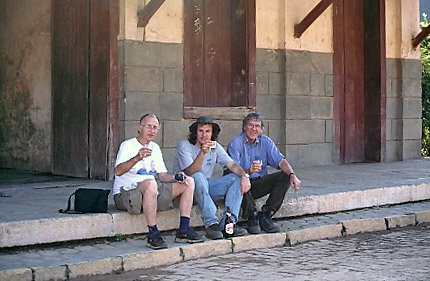

pioneer trees - quaresmeira (*) |

pioneer trees |

pioneer trees |

pioneer trees with fedegoso (* *) ( * ) Tree of Melastomataceae family (* *) Tree of Leguminosae family |

| ON:

The bromeliads are the first to come, before the orchids, aren't they? David: On the ground. The ridges are simple garden of bromeliads. During the dry period, we studied a big tree which fell down, there were 250 medium size bromeliads. There were another ones, enormous and small but we just took a half dozen of the medium and found out that in the crown, they carry off 2 liters of water. With 250 on the tree, obviously, you have 500 liters. Thus, if we add the other epiphytes, orchids, genesriaceae, lily, we can calculate that each one of those trees has 700 liters of suspended water. If you project it by hectare and do the average of 30 big trees by hectare, you will reach 21.000 liters of suspended water. If you measure it in kilometers squared of anticline, from Paraíba do Sul until São Fidelis in the north, where existed the more dense, the most beautiful ombrophilous forest, we can realize that there was a suspended sea, a suspended lake, not too deep, controlling the climate, controlling everything and allowing the exuberance of the forest. With the destruction provoked by the coffee's barons, the sea turn into backwoods and this was the worst thing that happened. It was not the erosion nor the end of the forest itself but the fact that the suspended sea, that everything which gave the climate, gave everything, has been taken away. The ground should be exploited by sections, instead of taking everything out like they did. That was we found out. I think that nobody has projected things like this. When you stay over something for 30 years, you start to get things. ON: In a certain way, you have participated to Atlantic Forest Program (Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro). David: We received members from Botanical Garden for five or six years to accomplish Atlantic Forest Program. The program has been done and this is the most important. The base is done giving an enormous credibility in order to avoid the parcels of land in this area. We succeeded in eliminating this kind of thing. They did a survey about any kind of tree, sub-wood and soil but they didn't come to the conclusions I am drawing now. Isabel: The Botanical Garden decided, this is very important, that our natural reserve, in Macaé de Cima, is a mirror to another areas in the state. David: They told that the vegetal earth in the original forest has at about 30% of sand, without capacity to hold water back. The problem is that they forgot that the soil does not hold by itself but the interlacing of capillary roots does. The key to conserve out water is not the fact that the soil is clay or sandy, the key is the root system. If you don't have humidity, you don't have a useful ground. Not only the forest hold the water down but also the bromeliads hold the water up. That is the key of our neotropical system. In the book, we emphasize this and the introduction talks about this interlacing. This is not political or socially understood and our rivers became flush toilets. |

| ON:

This gives the balance. David: It gives the balance and the sustenance of the ecosystem. Bel: Not only the orchids, but also to animals... David: Yes, to the ecosystem as a whole. The flowers are the flags that show something. If there are not orchids, the forest is not enough mature. For example, you don't find orchids in shrubbery forests. We found it out in a hard way when we started to look for orchids in the anticline, I walked down big areas of shrubbery forest, without any original forest, only just those relic-trees you met sometimes in the middle of the pasturage, enormous absolutely replete bromeliads, filled of orchids. |

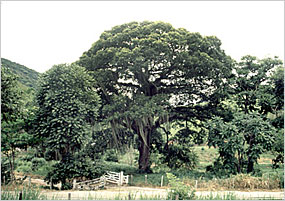

| This

pink Jequitibá, for example, grew up like this because there is not

anything around. General, it grows almost vertically in the wood. For some reason, they weren't taken off. ON: Perhaps for a practical reason, to give shade to the cattle, for example. |

|

|

David:

In many areas, around the farmhouses, there enormous imperial palms, filled

with orchids and also wonderful trees, true relics. Obviously when you

are writing about the effects of the coffee's barons allied to our 30-years

experience, you start to deeply see the terminal effects, as we can say.

|

|

|