|

Botanist and Professor at the University of São Paulo.

He develops studies with taxonomy, evolution and reproduction of plants, mainly orchids.

Throughout his career he has been dedicated to studies involving Neotropical Vanilla.

Department of Biology, Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters, University of São Paulo, Av. Bandeirantes 3900, 14040-901, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

For correspondence: epansarin@ffclrp.usp.br

|

Vanilla includes about 130 species that are distributed throughout the tropical regions of the Americas, Asia and Africa.

In Brazil, this important orchid genus is represented by approximately 35 species.

Although cultivated for centuries due to the importance of its fruits for the industry and gastronomy, aspects related to the natural history of vanillas have still been little explored. However, recent studies based on extensive field and laboratory work have changed this scenario.

For a long time, pollen transfer in Vanilla has been attributed to a food deception system.

In the food decoy system, flowers commonly have characteristics common to those found in species that offer some kind of floral reward. However, the resource is not produced and pollinators are mistakenly attracted to the flowers. Although mistaken pollination can indeed occur in Vanilla (Pansarin & Pansarin 2014), at least as far as Neotropical species is concerned, this condition is uncommon and appears to have arisen from nectariferous ancestors (Pansarin & Ferreira 2022).

Neotropical Vanillas form two well-supported groups (clades).

One of them includes the thin-leaved, reticulated Vanilla, such as V. edwalli, V. dietschiana, V. arcuata and V. angustipetala.

Vanilla edwalli

Among the Vanilla with reticulate leaves, data are very scarce.

There are reports of bees of the genus Xylocopa as floral visitors to V. mexicana and V. edwallii. However, a detailed study involving populations of V. edwallii in the interior of the State of São Paulo revealed that the flowers of this species are pollinated by bees of the genus Epicharis (Pansarin et al. 2014).

In this study, the production of floral resources to pollinators was not detected. However, recent research has shown that many species known to be mistakenly pollinated may reveal the offering of some sort of resource. Therefore, it is very important that studies on pollination biology are based on the use of different methods of analysis, and that data are collected from more than one population (Pansarin et al. 2022).

For the Neotropical clade that includes fleshy-leaved species, pollinator data, although sparse, are available for many species.

Within this large group, Vanilla palmarum, which occurs as an epiphyte on palm trees, is pollinated by hummingbirds that visit the flowers in search of nectar.

A study carried out involving populations from Amazonas and Maranhão revealed that the flowers produce nectar, which is accumulated in a narrow tube (nectariferous chamber) formed by the union of the lip base with the flower column.

(Pansarin & Ferreira 2022). |

Detail of a Vanilla palmarum flower showing the accumulation of nectar in the nectariferous chamber |

Detail of the lip of Vanilla palmarum showing the longitudinal depression responsible for directing the hummingbird's beak to the nectariferous chamber.

Detail of the lip of Vanilla palmarum showing the longitudinal depression responsible for directing the hummingbird's beak to the nectariferous chamber. |

Vanilla palmarum is highly adapted for bird pollination. The flowers are yellow in color and do not emit any kind of fragrance. In addition, the central portion of the lip has a longitudinal channel that acts as a guide, directing the hummingbirds' beak to the nectariferous chamber (Pansarin & Ferreira 2022).

The remaining Neotropical species form a large group whose flowers are odoriferous and pollinated by males of solitary bees (euglossine males).

The relationship between male euglossine bees and Vanilla flowers has been observed since the first studies conducted by Robert Dressler in the 1960s (see Pansarin 2016, 2019).

|

These bees are attracted to vanilla flowers due to the volatilization of aromatic compounds that are produced by secretory cells present in the sepals and inside the lip (osmophores; Pansarin 2021).

Euglossine males collect the lipophilic substance that volatilizes (perfume) with brush-like structures present on the forelegs. Later, the bees transfer the collected substances to the posterior tibias, in structures called corbiculae, where they are stored.

The fragrances collected by the males are used during the courtship process and also for territorial defense.

Although floral scent is a collectable resource for euglossine males, the pollination process occurs when bees enter the floral tube formed by the lip and column in search of nectar (Pansarin 2016, 2019).

|

Eulaema nigrita males collecting floral fragrances on the sepals of a Vanilla pompona flower. |

Inside the lip it is also possible to observe the presence of osmophores. However, the narrow floral tube seems to derail the bees' fragrance-gathering behavior. In fact, the bees that are observed entering the lip appear to be interested in nectar, not in collecting fragrances. The osmophores present in the lip act as resource guides, as is common in plants pollinated by biotic agents.

In summary, although Neotropical Vanillas have long been considered to be pollinated by mistake of food, the pollination system of most of them is based on the provision of two types of floral resources, nectar and perfume (Pansarin 2016, 2019, 2021; Pansarin & Ferreira 2022).

Vanilla seed dispersal has been a topic of debate since the beginning of studies involving orchids.

Vanilla seeds as well as a few other basal genera within this family have characteristics common to those dispersed by animals (endozoochory; e.g. Pansarin 2022; Pansarin & Suetsugu 2022).

As is known, the seeds of most orchid species are tiny and dispersed by the wind (anemochory).

In an experimental study involving six Neotropical Vanilla species, it was proved that birds can act as seed dispersers in the genus (Pansarin 2022). that is, for germination to take place at the beginning of the rainy season, the seeds need to pass through the animals' digestive tract (Pansarin 2022).

In another study involving Vanilla dispersers, this time under natural conditions, it was observed that in addition to diurnal birds, nocturnal mammals (rats and marsupials) can also act in seed dispersal, at least in species with dehiscent fruits (which open and expose the seeds). seeds; Pansarin & Suetsugu 2022).

|

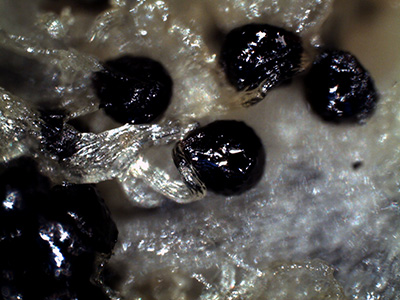

Vanilla bahiana fruit in cross section showing the seeds |

The fruit wall has large amounts of calcium oxalate crystals. These crystals can cause mammalian death in two ways: by asphyxiation, or when converted to oxalic acid (which is toxic to mammals) during the digestion process (Pansarin 2022; Pansarin & Suetsugu 2022).

The fruits of some Vanilla species when ripe show a very striking yellow/black color contrast that seems to be efficient in attracting birds during the day. |

Ripe fruit of Vanilla bahiana showing the dehiscence region with contrasting yellow/black color. |

Gracilinanus agilis (Cuíca) feeding on the endocarp of a Vanilla bahiana fruit. |

However, Vanilla fruits are commonly very aromatic and attract mammals at night.

Vanilla fruits are rich in lipophilic compounds (fats), sugars, and proteins (Pansarin & Suetsugu 2022).

Ongoing studies show that not only species belonging to the “aromatic clade” (i.e. euglossinophilic clade; Pansarin & Ferreira 2022) produce fragrant fruits.

Some species of Vanilla with reticulate leaves can also produce very fragrant fruits whose seeds are dispersed by animals. |

References

Pansarin ER (2016) Recent advances on evolution of pollination systems and reproductive biology of Vanilloideae (Orchidaceae). Lankesteriana16: 255-267.

Pansarin ER (2019) The use of multiple data sources to elucidate the identity of Brazilian vanillas (Vanilloideae, Orchidaceae). In: Proceedings, 22nd World Orchid Conference. Asociación Ecuatoriana de Orquideologia, Guayaquil, Ecuador (pp. 162-167).

Pansarin ER (2021) Vanilla flowers: much more than food-deception. Bot J Linn Soc 198: 57–73.

Pansarin ER (2022) Unravelling the enigma of seed dispersal in Vanilla. Plant Biol 23: 974-980.

Pansarin ER, Ferreira AWC (2022) Evolutionary disruption in the pollination system of Vanilla (Orchidaceae) Plant Biol 24: 157-167.

Pansarin ER, Suetsugu K (2022) Mammal-mediated seed dispersal in Vanilla: its rewards and clues to the evolution of fleshy fruits in orchids ESA Ecology (on press)

Pansarin ER, Pansarin LM (2014) Floral biology of two Vanilloideae (Orchidaceae) primarily adapted to pollination by euglossine bees. Plant Biol16:1104–1113.

Pansarin ER, Aguiar JMRBV, Pansarin LM (2014) Floral biology and histochemical analysis of Vanilla edwallii Hoehne (Orchidaceae: Vanilloideae): an orchid pollinated by Epicharis (Apidae: Centridini). Plant Sp Biol 29:242–252.

Pansarin ER, Pedro SR, Davies KL, Stpiczyńska M (2022), Evidence of floral rewards in Brasiliorchis supports the convergent evolution of food-hairs in Maxillariinae. Am J Bot (on press)

|

![]()